Moroccan Military Forum alias FAR-MAROC

Royal Moroccan Armed Forces Royal Moroccan Navy Royal Moroccan Air Forces Forces Armées Royales Forces Royales Air Marine Royale Marocaine

|

|

| | US Navy |  |

|

+39jf16 osmali augusta RED BISHOP jonas Inanç leadlord godzavia farewell klan PGM yassine1985 mox brk195 lida Spadassin GlaivedeSion Gémini juba2 Nano thierrytigerfan FAMAS Yakuza Northrop reese MAATAWI H3llF!R3 Mr.Jad Fremo Leo Africanus Fahed64 Seguleh I hakhak Viper gigg00 aymour Samyadams naourikh SnIpeR-WolF [USAF] 43 participants | |

| Auteur | Message |

|---|

SnIpeR-WolF [USAF]

2eme classe

![SnIpeR-WolF [USAF]](https://2img.net/u/1312/35/62/43/avatars/522-6.jpg)

messages : 35

Inscrit le : 22/03/2008

Localisation : France

Nationalité :

|  Sujet: US Navy Sujet: US Navy  Sam 22 Mar 2008 - 17:06 Sam 22 Mar 2008 - 17:06 | |

| Rappel du premier message :Bonjour/Bonsoir ; Alors, je vous présente quelques portes avions USA : USS Carl Vinson  USS Harry S Truman  USS Nimitz  USS Eisenhower  USS George H. W. Bush  USS Kity Hawk .jpg) USS Wasp  USS Tarawa  USS Saipan

_________________

Marocain, et fier de l'être.

| |

|   | |

| Auteur | Message |

|---|

MAATAWI

Modérateur

messages : 14757

Inscrit le : 07/09/2009

Localisation : Maroc

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Mar 19 Jan 2010 - 15:40 Mar 19 Jan 2010 - 15:40 | |

| - Citation :

Navy analysis finds unexpectedly high costs for F-35, continuing program's bad news

Storms and turbulence continue to buffet Lockheed Martin’s F-35 joint strike fighter program, as observers in the military, political and investment arenas keep a close watch for progress — or the lack of it.

Close on the heels of reports that the Pentagon plans to cut F-35 orders over the next several years, an internal Navy study leaked last week drove a new wave of speculation in the defense and aerospace industries.

The study, by the Navy’s aviation arm, says the cost to buy and operate that service’s version of the F-35 will be dramatically higher than predicted — 40 percent more than existing aircraft — and will put a serious squeeze on future budgets.

The report follows continued reports of F-35 development delays. It was also reported Jan. 6 that the 2011 Pentagon budget, set for release Feb. 1, will cut planned F-35 purchases.

The validity and accuracy of the Navy’s cost analysis is open to debate. Navy officials did not comment or elaborate on the study, but several veteran defense observers said it was a sign that many in the naval aviation ranks remain less than committed to buying the sea service’s version of the F-35.

By allowing the cost study to leak widely, "the Navy seems to be putting a log on the fire and prepping the battlefield to bail out" of the F-35 program, said Winslow Wheeler, director of the Strauss Military Reform Project and former longtime Senate defense staff member.

Loren Thompson, a defense analyst with the Lexington Institute and a consultant to Lockheed and other defense contractors, said the Navy study "is preposterously wrong. It makes no sense."

Thompson does not think that the JSF program is in serious trouble but said the study reflects the continued ambivalence of many Navy officials toward the F-35.

That brings up ominous historical parallels. The Navy, as Fort Worth knows too well, has a history of abandoning joint aircraft development programs.

In the 1960s, the Navy spurned buying a version of General Dynamics’ F-111 in favor of the Grumman F-14. A decade later, Navy leaders bailed out of plans for a carrier-based version of the F-16 to get their own plane, the F/A-18.

Even today, "a lot of people in naval aviation have high regard for the Boeing legacy fighter, the F/A-18 Super Hornet," Thompson said. "The Super Hornet is a fine plane, but it simply cannot survive in the future fighting against an enemy like China. The Navy will need the stealth of the F-35 to penetrate heavily defended air space."

Others around the globe, however, take the study seriously.

Peter Goon, a former Australian military test pilot who is a critic of the F-35, called the Navy’s figures "highly credible." Based on studies by his group, Air Power Australia, Goon said, "The results of this study are on the conservative side."

Lockheed’s public affairs office in Fort Worth issued a statement last week saying the Navy study’s cost figures "are an independent assessment and are not definitive." The company’s statement reiterated Lockheed’s position on the F-35 program, which essentially holds that the airplane is designed to be easier and less costly to maintain and operate than the existing aircraft it is supposed to replace.

"The F-35 program is committed to working with the JSF Program Office and Naval Air Systems Command to develop the most accurate estimate possible of F-35 life-cycle support," the company’s statement said.

Lockheed is the prime contractor on the F-35 and plans to build most of the planes in Fort Worth. About 7,000 local Lockheed employees work on the program, which is struggling to get airplanes built and into flight testing.

Several Wall Street analysts recently downgraded their ratings on Lockheed’s shares (ticker: LMT) over worries that the F-35 program’s delays and technical problems will result in lower profits for the next few years or even endanger the company’s long-term outlook.

Peter Arment, an aerospace industry analyst for the Broadpoint AmTech investment firm, downgraded Lockheed stock from buy to neutral because of the Pentagon’s plan to significantly reduce orders in the next few years.

From an investment standpoint, Arment said, the delays in production will likely mean lower-than-anticipated profits for Lockheed. Arment doesn’t think that the F-35 program is in grave political danger, but the continuing delays and problems are a source of concern. source:www.star-telegram.com | |

|   | | Yakuza

Administrateur

messages : 21656

Inscrit le : 15/09/2009

Localisation : 511

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Mer 20 Jan 2010 - 0:07 Mer 20 Jan 2010 - 0:07 | |

| - Citation :

- Sikorsky Aircraft Corp., Stratford, Conn., was awarded on Jan. 15, 2010 a $600,697,952 firm-fixed-price contract for the funding of Fourth Program Year of multi-year contract for Navy Lot 12 consisting of 18 each MH-60S Sea Hawk helicopters and for Navy Lot 8 consisting of 24 each MH-60R Sea Hawk helicopters for the Navy and also tooling: program systems management; and technical publications. Work is to be performed in Stratford, Conn., with an estimated completion date of Dec. 31, 2012. One bid solicited with one bid received. U.S. Army Aviation & Missile Command, AMSAM-AC-BH-A, Redstone Arsenal, Ala., is the contracting activity (W5RGZ-08-C-0003).

_________________  | |

|   | | Fremo

Administrateur

messages : 24819

Inscrit le : 14/02/2009

Localisation : 7Seas

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

| |   | | Fremo

Administrateur

messages : 24819

Inscrit le : 14/02/2009

Localisation : 7Seas

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Jeu 21 Jan 2010 - 18:57 Jeu 21 Jan 2010 - 18:57 | |

| | |

|   | | MAATAWI

Modérateur

messages : 14757

Inscrit le : 07/09/2009

Localisation : Maroc

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Ven 22 Jan 2010 - 12:24 Ven 22 Jan 2010 - 12:24 | |

| - Citation :

De graves problèmes sur des bâtiments de l’US Navy

Les ingénieurs de l’US Navy font face à de graves problèmes découverts à bord de bâtiments construits dans les chantiers navals Gulf Coast de Northrop Grumman — soudures défectueuses, problèmes hydrauliques et un moteur défaillant — dans le dernier épisode de la saga des difficiles relations entre la Navy et son principal chantier naval.

Les inspecteurs vérifient à nouveau toutes les soudures de tous les navires construits ces dernières années à Avondale ou Pascagoula, y compris des destroyers et des navires amphibies, après avoir découvert tellement de problèmes que tous les soudeurs et contrôleurs qualité des 2 chantiers ont dû être requalifiés.

Les responsables de la Navy n’avaient pas jeudi d’information sur le nombre de personnes ayant dues être requalifiées ou sur celui de personnes n’ayant pas récupéré leur qualification et renvoyées. Le processus de requalification s’est déroulé l’été dernier lorsque les premiers problèmes ont été découverts.

Une question importante est de savoir comment des inspecteurs du NavSea ont pu approuver des travaux qui ont ensuite été rejetés lors de nouveaux contrôles.

Dans la plupart des cas, les problèmes révélés jeudi n’étaient pas urgents. Il s’agit par exemple de soudures ne respectant pas les critères de la Navy pour la résistance au choc. Mais dans certains cas, les problèmes pourraient avoir un impact sur l’activité opérationnelle des bâtiments. Des inspecteurs vérifient ainsi tous les bâtiments amphibies de la classe San Antonio pour découvrir ce qui a causé les problèmes hydrauliques sur de nombreux navires et a endommagé les roulements d’un moteur sur le plus récent, le New York.

En plus de problèmes de soudure communs à toute la classe, le New York a aussi des problèmes spécifiques sur l’un de ses moteurs, qui a un vilebrequin cintré qui devra être remplacé selon une procédure qui n’a jamais été tentée auparavant. source:corlobe.tk | |

|   | | Fremo

Administrateur

messages : 24819

Inscrit le : 14/02/2009

Localisation : 7Seas

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Mer 27 Jan 2010 - 0:17 Mer 27 Jan 2010 - 0:17 | |

| Intéressant point de vue sur l'avenir de l'US Navy, et deux points clefs: le remplacement des Ohio, et la défense anti-missile.. à retenir aussi que la flotte US a diminué en terme de nombre des batiments de presque 50% entre 1980 et 2009, et le nombre va légérement augumenter d'ici 2011... Bonne lecture  - Citation :

- CBO TESTIMONY

Statement of Eric J. Labs

Senior Analyst for Naval Forces and Weapons

The Long-Term Outlook for the U.S. Navy’s Fleet

before the Subcommittee on Seapower and Expeditionary Forces

Committee on Armed Services U.S. House of Representatives

January 20, 2010

Mr. Chairman, Congressman Akin, and Members of the Subcommittee, I appreciate the opportunity to appear before you today to discuss the challenges that the Navy is facing in its plans for building its future fleet. Specifically, the Subcommittee asked the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to examine three matters: the Navy’s draft shipbuilding plan for fiscal year 2011, the effect that replacing Ohio class submarines with a new class of submarines will have on the

Navy’s shipbuilding program, and the number of ships that may be needed to support ballistic missile defense from the sea. CBO’s analysis of those issues indicates the following:

■ If the Navy receives the same amount of money for ship construction in the next 30 years that it has over the past three decades—an average of about $15 billion per year in 2009 dollars—it will not be able to execute its fiscal year 2009 plan to increase the fleet from 287 battle force ships to 313.1 As a result, the draft 2011 shipbuilding plan drastically reduces the number of ships the Navy would purchase

over 30 years, leading to a much smaller fleet than either the one in the 2009 plan or today’s fleet.

■

The draft 2011 shipbuilding plan increases the Navy’s stated

requirement for its fleet from 313 ships to 324, but the production schedule in the plan would buy only 222 ships, too few to meet the requirement. The Navy’s current 287-ship fleet consists of 239 combat ships and 48 logistics and support ships. The 2009 plan envisioned expanding the fleet to a total of 322 ships by 2038: 268 combat ships and 54 logistics and support ships. In contrast, under the draft 2011 plan, the fleet would decline to a total of 237 ships by 2040: 185

combat ships and 52 logistics and support ships.2

■

CBO’s preliminary estimate is that implementing the draft 2011

shipbuilding plan would cost an average of about $20 billion per year for all activities related to ship construction (including modernizing some current surface combatants and refueling ships’ nuclear reactors). A more detailed estimate will follow after the Navy formally submits its final 2011 plan to the Congress in February with the President’s budget request.

■

Replacing the 14 ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) of the Ohio class —which are due to start reaching the end of their service lives in the late 2020s—with 12 new SSBNs could cost about $85 billion. If the Navy received that amount in addition to the resources needed to carry out the draft 2011 plan (which includes funding for those new submarines),

it could probably purchase the additional ships identified in the "alternative construction plan" that accompanied the draft 2011 plan, because CBO’s preliminary estimate of the cost of that alternative plan is an average of about $23 billion per year over 30 years.

■

Sea-based ballistic missile defense, a relatively new mission for the Navy, could require a substantial commitment of resources. That commitment could make it difficult for the Navy to fund other ship programs.

Before discussing those issues, however, let me briefly recap CBO’s analysis of the 2009 shipbuilding plan as a point of departure for examining the draft 2011 plan.

The Navy’s 2009 Shipbuilding Plan and the Effects of Extending Current Funding Levels

For much of the past decade, the Navy spent an average of about $13 billion a year (in 2009 dollars) on shipbuilding: approximately $11 billion to construct new ships and $2 billion to refuel nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and submarines and to modernize surface combatants. In a report to this Subcommittee, CBO estimated that carrying out the Navy’s 2009 plan to build and sustain a 313-ship fleet would cost far more than that: a total of about $800 billion (in 2009 dollars) over 30 years—or an average of almost $27 billion a year (see Table 1).3 Those costs would include the purchase of 296 new ships, nuclear refuelings of aircraft carriers and submarines, and the purchase of mission modules for littoral combat ships (LCSs). New-ship construction alone would cost about $25 billion a year, including new ballistic missile submarines.

The Navy’s cost estimate for implementing the 2009 plan was only slightly lower than CBO’s projection. The Navy estimated that it would need to spend a total of about $750 billion over the 30-year period of the 2009 plan—or an average of about $25 billion per year for all shipbuilding activities and about $23 billion per year for new-ship construction alone. In contrast to the similarity between CBO’s and the Navy’s estimates for the 2009 plan, CBO’s estimates for the 2007 and 2008 shipbuilding plans were approximately 30 percent to 35 percent higher than the Navy’s estimates (which were substantially smaller than the service’s estimate for its 2009 plan).

Historical Funding for Ships

Over the past 30 years, the distribution of the Navy’s shipbuilding budget among the major categories of ships has been fairly stable.

Surface combatants have received about 37 percent of shipbuilding funds; submarines, 30 percent; aircraft carriers, 16 percent; amphibious ships, 10 percent; and logistics and support ships, 7 percent. The 2009 shipbuilding plan envisioned increasing the share of funding devoted to submarine construction from 30 percent to an average of 38 percent over the next 30 years, CBO estimated—largely at the expense of logistics and support ships and surface combatants (see Table 1). That projected increase resulted mainly from including the costs of replacing the Navy’s SSBNs (which are discussed in more detail later in this testimony). Table 1 illustrates some of the challenges the Navy faces in funding its ship accounts. Average annual spending for surface combatants would have to rise by 80 percent—and spending for submarine construction would need to more than double—for

the Navy to buy the major combat ships included in the 2009 plan.

One factor that contributes to the Navy’s funding challenges is the historical trend of rising average costs per ship (see Table 2).

During the 1980s, the era of the Reagan Administration’s military buildup, the Navy paid an average of about $1.2 billion (in 2009 dollars) for a new ship. The new ships in the 2009 plan would cost an average of about $2.5 billion apiece by the Navy’s estimate, or $2.7 billion apiece by CBO’s estimate. The most recent information on actual ship purchases comes from the 2010 defense appropriation act,which allocates nearly $15 billion to buy seven ships, for an average cost of about $2.1 billion each. That figure is smaller than the estimates of per-ship costs under the 2009 plan because five of the seven ships purchased in the 2010 appropriation act (two LCSs, two T-AKE logistics ships, and one high-speed vessel) are relatively inexpensive, costing no more than about $600 million apiece. The 2010 shipbuilding appropriation illustrates how a fleet composed of less expensive ships could stop the trend of growing average costs per ship, although it could result in a less capable fleet than the more expensive ships in the Navy’s 2009 plan.

The rise in average ship costs over time may stem from several

factors:

■

When the Navy buys a new generation of ships, it improves their

capabilities, thus driving up their costs.For example, the Arleigh Burke class destroyer, which was first built in the 1980s, is much more capable—and much more expensive—than the preceding Spruance class destroyer, which was built mainly in the 1970s. Likewise, future versions of the Arleigh Burke class destroyer configured to perform ballistic missile defense are likely to be more costly than existing ships.

■

Over the past two decades, increases in labor and materials costs to build naval ships in the United States have outstripped inflation in the economy as a whole. Specifically, the cost of building ships has been rising about 1.4 percent faster per year than the prices of final goods and services in the U.S. economy (as measured by the gross domestic product deflator).

■

As average ship costs have increased, the Navy has bought fewer ships.

However, the fixed overhead costs at naval shipyards may not have declined at the same rate. Thus, with fewer ships being purchased, the average amount of fixed overhead costs per ship may have risen.

The numbers in Table 2 illustrate the decline in ship purchases over time. During the 1980s, the Navy bought an average of 17.2 ships per year in pursuit of a 600-ship fleet. By the 2000s, that number had fallen to 6.0 ships a year. To sustain the steady-state fleet of 313 ships envisioned in the 2009 plan, however, the Navy would need to buy 8.9 ships per year, under an assumption that the ships had an average

service life of 35 years.(A larger fleet of 324 ships, the reported goal of the draft 2011 plan, would require buying 9.3 ships per year over the long term.) To compensate for earlier years in which the Navy bought fewer than 8.9 ships per year, the 2009 shipbuilding plan would purchase 9.9 ships each year to achieve and maintain a 313-ship fleet.

The Effects of Current Budget Levels on the Future Fleet

Despite the large funding increases that would be necessary to carry out the 2009 plan, senior Navy officials have said in recent months that the service expects to make do with $13 billion to $15 billion per year for its future shipbuilding. In October 2009, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Ship Programs, Allison Stiller,said she thought "$13 billion [per year] is about right." Severalweeks later, however, the Under Secretary of the Navy, Robert O. Work, stated, "We think we can do what we need on $15 billion a year."

Those funding levels—which represent about 50 percent to 60 percent of the amount required to fund the 2009 shipbuilding plan—are similar to what the Congress has appropriated in recent years. In both 2008 and 2009, the Navy received about $14 billion for ship construction, in each case more than the Administration had requested. For 2010, the President’s budget requested $14.9 billion for ship construction, and the Congress appropriated $15.0 billion.

CBO compared the number of ships that could be purchased with annual budgets of either $13 billion ($390 billion over 30 years) or $15 billion ($450 billion over 30 years) under three scenarios for average ship costs: $2.1 billion per ship, as in the 2010 defense appropriation; $2.5 billion per ship, as in the Navy’s estimate for the 2009 plan; and $2.7 billion per ship, as in CBO’s estimate for the 2009 plan.9 That plan envisioned buying a total of 296 ships over 30 years. Under the constrained budgets, roughly one-half to three-quarters of that number of ships could be purchased, depending on the average cost per ship (see Figure 1). At the bottom end of the range, a $13 billion annual budget would buy 144 ships over 30 years at an average cost of $2.7 billion apiece. At the top end of the range, a $15 billion annual budget would yield 214 new ships over 30 years if their cost averaged $2.1 billion.

The ship purchases under those scenarios would not be large enough to replace all of the Navy’s current ships as they reach the end of their service lives in coming years. Consequently, with those annual budget levels and average ship costs, the size of the Navy’s fleet would decline over the next three decades from 287 ships to between 170 and 240 ships. Specifically, if Navy ships cost an average of $2.1 billion apiece, the battle force fleet would fall to about 270 ships by 2025 with a $15 billion annual budget or to 250 ships with a $13 billion budget (see Figure 2). However, if the cost per ship averaged $2.7 billion, the fleet would decline to about 230 ships by 2025 under the lower budget level or to about 240 ships under the higher level. By 2038, the last year of the 2009 shipbuilding plan, the effect on the fleet would be more pronounced. The high end of the range (a $15 billion shipbuilding budget and an average cost of $2.1 billion per ship) would be 240 ships, but the low end (a $13 billion budget and $2.7 billion per ship) would yield just 170 ships—60 percent of the size of today’s fleet.

The Navy’s Draft 2011 Shipbuilding Plan

The Subcommittee asked CBO to analyze the procurement and inventory tables from a draft of the Navy’s shipbuilding plan for fiscal year 2011. The six tables, which have not been officially released, were published at InsideDefense.com.

■

One table shows an increase in the target size of the battle force fleet from 313 ships to 324. The target for large surface combatants (cruisers and destroyers) has been raised from 88 to 96, and the desired number of support ships has nearly doubled from 20 to 39.

Those increases are partly offset by deleting the requirements for future maritime prepositioning ships and guided missile submarines.

■

Other tables show more details of the draft 2011 plan: construction and funding profiles for Navy ships from 2011 to 2015 and the construction profile and inventory of battle force ships from 2011 to 2040. Those profiles indicate that the Navy envisions buying 222 ships (including 12 SSBNs) in the next 30 years under the draft 2011 plan, compared with 296 ships under the 2009 plan.11 With those purchases, the size of the battle force fleet would peak at 312 ships in 2021 and then decline steadily to 237 ships by 2040. (In comparison, the 2009 shipbuilding plan envisioned a fleet of 322 ships in 2038, the last year of its projection period.)

■

The remaining tables show the construction profile and inventory of battle force ships through 2040 under an "alternative construction plan." That plan assumes that the Navy receives funding to purchase a new class of SSBNs in addition to the full funding needed for the draft 2011 plan. The alternative plan would purchase 278 ships between 2011 and 2040. Again, the battle force fleet would peak at 312 ships in 2021, but thereafter it would decline only to a range of 286 to 291 ships between 2030 and 2040, about the same size as today’s fleet.

Most of the cuts under the draft 2011 plan and the alternative construction plan come from the Navy’s combat ships: surface combatants, submarines, aircraft carriers, and amphibious ships. Under the 2009 shipbuilding plan, the Navy would have purchased 245 combat ships. That number falls by 32 percent (to 166) in the draft 2011 plan and by 16 percent (to 207) in the alternative plan .

Thus, by 2038, the draft plan would produce a fleet of 189 combat ships, compared with 239 today or 268 under the 2009 plan. The alternative construction plan would yield a fleet of 222 combat ships.

a. The "alternative construction plan" included in draft Navy

documents resembles the draft 2011 plan but with additional resources provided to fund the replacement of the Navy’s ballistic missile submarines; the costs of that replacement could otherwise displace some ships from the construction plan.

b. The Navy currently has 239 combat ships and 48 logistics and

support ships, for a total fleet of 287 ships.

c. Because the Navy’s long-term shipbuilding plans typically cover 30 years, 2038 is the final year of the 2009 plan. (The 2011 plans run through 2040.)

It is not clear from available information what the Navy believes the draft 2011 plan will cost. If the service assumed an average annual shipbuilding budget of $15 billion over the 30-year period of the plan, the 222 ships purchased under the plan would imply an average cost of $2.0 billion per ship. A $13 billion annual shipbuilding budget would imply an average per-ship cost of $1.8 billion. Both of those figures are much smaller than the $2.5 billion per ship implied by the 2009 plan. In the alternative 2011 construction plan, which envisions that the Navy will receive an extra $85 billion to fund its new class of SSBNs, the service buys 56 additional ships. Under that plan, the $15 billion and $13 billion budget levels would imply average per-ship costs of $1.9 billion and $1.7 billion, respectively.

CBO’s preliminary assessment of the draft 2011 plan suggests that it would cost considerably more than $15 billion per year to implement.

On the basis of the limited information available in the press, CBO estimates that carrying out all of the shipbuilding activities in the draft plan would cost an average of about $20 billion a year (in 2010 dollars) between 2011 and 2040. The alternative 2011 construction plan would cost an average of about $23 billion per year. Those estimates may change depending on the details that are in the official 2011 plan when the Navy submits it next month.

One notable feature of the draft plan is that the Navy appears to be budgeting amounts for the littoral combat ship that would greatly exceed the Congressionally mandated cost cap for those ships. The cap, which is adjusted each year for inflation, is currently $480 million per vessel (excluding outfitting costs, postdelivery costs, and costs for the mission modules that LCSs will carry). According to the draft tables available for the 2011 plan, the Navy hopes to buy two LCSs in 2011 for a total of $1.2 billion, another two in 2012 for $1.2 billion, three in 2013 for $1.8 billion, four in 2014 for $2.6 billion, and four more in 2015 for $2.6 billion (all in then-year dollars). Thus, the total amount budgeted for those 15 LCSs between 2011 and 2015 is $9.4 billion, whereas the adjusted cost cap would permit no more than $7.8 billion.

The Cost of Replacing Ohio Class Ballistic Missile Submarines

The Navy’s Ohio class submarines, which carry Trident ballistic missiles, are the sea-based leg of the U.S. strategic triad for delivering nuclear weapons. Those submarines will start to reach the end of their service lives in the late 2020s. Under the draft 2011 plan, replacing the Ohio class SSBNs would consume a significant share of the resources devoted to ship construction over the next 30 years.

The Navy’s 2009 plan included a requirement for a fleet of 14 SSBNs, but it envisioned buying only 12 of those submarines, two fewer than in the 2007 and 2008 shipbuilding plans. The tables available for the draft 2011 plan suggest that the Navy has reduced its requirement for SSBNs to 12 and that it intends to buy that number of replacements for the Ohio class submarines over the next three decades.

The Navy’s Estimates

The design, cost, and capabilities of that replacement class—currently called the SSBN(X)—are among the most significant uncertainties in the Navy’s and CBO’s analyses. The Navy’s 2007 and 2008 shipbuilding plans assumed that the first SSBN(X) would cost $4.3 billion and that subsequent ships in the class would cost about $3.3 billion each,implying an average cost of about $3.4 billion per submarine. The 2009 plan explicitly excluded the costs of the SSBN(X), although it included 12 of the submarines in its projection of future inventories.

Press reports now indicate that the Navy expects a class of 12 SSBN(X) s to cost a total of about $80 billion, an amount that the Navy said it determined by inflating the cost of the original Ohio class to today’s dollars. That total implies an average cost of about $6.7 billion per submarine.13 The first SSBN(X) would be authorized in 2019 (although advance procurement money would be needed in 2017 and 2018 for long-lead items such as the ship’s nuclear reactor). The second submarine would be purchased in 2022, followed by one per year from 2024 to 2033.

CBO’s Estimates

Many Navy and industry officials involved with submarine warfare or construction expect that an SSBN(X) would be substantially smaller than an Ohio class submarine. However, that does not necessarily mean it would be cheaper to build, even with the effects of inflation removed.

Since 1991, when the last Ohio class submarine was authorized, the submarine industry has improved its design and construction processes.

Both General Dynamics’s Electric Boat shipyard and Northrup Grumman’s Newport News shipyard use more-modern construction techniques and have become more efficient. Those changes suggest that using the Ohio class as an analogy to estimate the future costs of the SSBN(X) could overstate costs.

At the same time, however, the factors described above that have caused average ship costs to grow over time also apply to submarines.

Growth in labor and materials costs in the submarine construction industry has outstripped general inflation. In addition, the capabilities of the Navy’s submarines have improved over the years,making them more expensive to produce. Finally, Ohio class submarines were built at a time when the Navy was constructing many more warships (including aircraft carriers at Newport News and submarines at both shipyards) than it is today, which suggests that those earlier submarines benefitted from having fixed overhead costs spread over more ships.

The growth in submarine costs over time can be seen by comparing the cost per thousand tons of the lead ship of U.S. submarine classes produced in the past 40 years (see Figure 3). In the 1970s, the Navy built the first Los Angeles class attack submarine and the first Ohio class ballistic missile submarine for about $350 million to $400 million per thousand tons of Condition A weight (a term analogous to lightship displacement on surface ships, which is the weight of the

ship excluding fuel, ammunition, crew, and stores). By the late 1980s and 1990s, the cost of the lead ships of the Seawolf and Virginia classes of attack submarines had more than doubled to $825 million to $850 million per thousand tons.

In most of its recent naval analyses, CBO has assumed that the SSBN(X) would carry 16 missile tubes instead of the 24 on existing submarines and would displace around 15,000 tons submerged—making it roughly twice as big as a Virginia class attack submarine but nearly 4,000 tons smaller than an Ohio class SSBN. On the basis of that assumed size —as well as the amount the Navy is currently paying for a Virginia class submarine and historical cost growth in shipbuilding programs—

CBO estimates that 12 SSBN(X)s would cost an average of $7.0 billion each (in 2010 dollars). The lead ship of the class could cost about $11 billion (including some nonrecurring items) when ordered in 2019.

In all, CBO expects a class of 12 SSBN(X)s to cost a total of about $85 billion.

The figures that the Navy is using now for the SSBN(X), as reported in the press, appear to align more closely with CBO’s estimates of the past three years than with the estimate that the Navy used in formulating its 2007 and 2008 shipbuilding plans. CBO’s estimate of $7.0 billion per submarine is slightly larger than the reported Navy figure of about $6.7 billion, which is twice the $3.4 billion average cost that the Navy assumed for the SSBN(X) in its 2007 and 2008 shipbuilding plans.

Ballistic missile submarines are more capable of surviving attacks than the other legs of the U.S. strategic triad, and they carry about half of the nation’s deployed nuclear warheads. Given that role, policymakers may regard replacing the Ohio class when it retires as the most critical part of the Navy’s shipbuilding plan. If those SSBNs were going to be replaced no matter what happened, and if the Navy received enough resources to pay for them above and beyond what it

might otherwise expect to allocate to shipbuilding, it could use the additional funding to buy more surface ships and attack submarines.

That is the presumed motivation behind the alternative construction plan that accompanied the draft 2011 plan. CBO’s estimate of the difference in costs between the draft 2011 plan and the alternative construction plan is $3 billion per year, or a total of about $90 billion (compared with the estimated $85 billion cost of 12 SSBN(X)s).

Under the alternative plan, that extra $90 billion would purchase 56 additional ships: 19 large surface combatants, 15 littoral combat ships, 4 attack submarines, 3 amphibious ships, and 15 logistics and support ships.

Surface Combatants Required to Support Ballistic Missile Defense

The Subcommittee asked CBO to evaluate the number of Aegis-capable surface combatants needed to perform the ballistic missile defense (BMD) mission in Europe. The answer could range from 3 to 15 depending on the rotation method the Navy used to provide ships for BMD patrols, which CBO assumed would require continuous coverage of the patrol areas.The Missile Defense Agency (MDA) is also concerned with a broader mission of providing missile defense to parts of the Middle East as well as to Europe, which would require additional patrol areas

needing continuous presence by BMD-capable ships. CBO estimated the number of ships required for missile defense—focusing on Europe first—using three possible rotation methods:

■

Traditional Rotation (5:1)—Under the Navy’s current deployment cycle for surface combatants, five ships (based in Norfolk, Va.) are necessary to keep one ship forward deployed in the European theater at all times. That cycle typically keeps ships deployed for six months at a time. After that, they spend 18 to 21 months in their home port while their crews rest and train and the ship undergoes maintenance in

preparation for the next six-month deployment (although during much of that time, the ship remains in a near-ready state to deploy quickly if necessary).Thus, at any point, roughly three of the five ships in the rotation will be in the early, middle, or late stage of their time in their home port, a fourth ship will be deploying to or from the theater of operations, and the fifth ship will be on-station in the

theater.

■

Rotating Crews (3:1)—In this method, which is similar to what the Navy is planning for littoral combat ships, three or four crews take turns operating three ships, one of which is forward deployed at any given time. Depending on the rotation model, a ship remains overseas longer than six months, and replacement crews are flown to its location in the theater to take over running it, while two other ships remain in

their home port in the continental United States for training and maintenance. That rotation method lets ships spend less overall time in transit to and from a theater and more time on-station. (In an experiment called Sea Swap conducted from 2002 to 2006, the Navy successfully rotated crews to individual destroyers while the ships were deployed overseas.)

■

Home Port in Theater (2:1 or 1:1)—The Navy could permanently base BMD-capable ships in Europe to provide an immediate response to a crisis or even full-time coverage of BMD patrol areas. The Navy counts ships that are based abroad as providing full-time overseas presence. If the Navy needed to ensure that one ship was always at sea providing ballistic missile defense, then a two-ship rotation might be necessary

to compensate for whatever time the first ship spent in its European home port for maintenance or other activities.

MDA has reported that sometime in the near term—the next five to seven years—ships may be stationed at three locations in European waters to provide sea-based ballistic missile defense in that theater against Iranian missile threats. Under the Navy’s traditional deployment cycle for surface combatants, a rotation of 15 ships would be needed to provide missile defense in Europe from three stations.

a. With five stations, one would be in the Persian Gulf, which would require a rotation ratio of 6:1 if the ships deployed from Norfolk,Va. With eight stations, two would be in the Persian Gulf.

For the broader and more demanding mission, MDA expects to need up to eight sea-based BMD stations in Europe and the Persian Gulf in the near term. For the longer term—10 years and beyond—MDA suggests that with improvements in BMD-related missiles, radars, and sensors, the number of stations at sea could be reduced to five. Under the Navy’s traditional deployment cycle, eight stations could require a rotation

of 42 ships, whereas five stations could require 26 ships.

The Navy could reduce the number of ships needed to provide full-time BMD presence in Europe by employing alternative crewing schemes or basing ships in the theater. For example, if the Navy used rotating crews along the lines of its Sea Swap experiments or its plan for LCSs, it might need only three ships to keep one operating full time in a designated BMD patrol area. In that case, only 24 ships would be necessary to support eight BMD stations in the near term, or 15 ships to support five stations over the long term. If the BMD requirement was limited to three stations around Europe, then just nine ships with rotating crews would be needed.

The BMD mission may be better suited to the use of rotating crews than traditional missions performed by surface combatants are. A BMD- capable surface combatant dedicated to the single mission of providing missile defense patrols would be analogous to the Navy’s SSBNs, which have the single mission of providing deterrent patrols at sea with nuclear missiles. Focusing on a single mission makes it easier for the

multiple crews of a single ship to maintain their proficiency when not on deployment. The Navy uses a dual-crew system for SSBNs, in which two crews take turns taking a submarine to sea to perform its mission.

That system allows strategic submarines to spend a majority of their service life at sea, compared with less than 30 percent for single-crewed attack submarines.

The Navy, however, does not currently envision dedicating ships to the single mission of missile defense. Instead, it plans to send BMD- capable ships on regular deployments to perform the full range of missions required of surface combatants, although some of the ships would operate in or near the BMD stations, available to perform that mission in the event of heightened tensions. Under such a system, using rotating crews on BMD-capable ships could prove far more challenging because the crews would need to maintain a high level of proficiency in many types of missions.

Alternatively, if the Navy was able to base BMD-capable ships

permanently in Europe or the Persian Gulf—as it does now in Japan to counter the threat of North Korean missiles—it might need as few as three to eight ships (one for each station). That estimate assumes that the Navy counts each of those ships as providing full-time presence on-station, in the same way that it considers ships based in Japan to be providing full-time presence even when they are in port undergoing routine maintenance. But if the Navy needed to guarantee

that one ship per station was at sea at all times, it would require a second ship for each of the three to eight stations, doubling the requirement. Those additional ships could also be based at home ports in the European theater.

1

"Battle force" is the term the Navy uses to describe its fleet, which includes all combat ships (surface combatants, aircraft carriers, submarines, and amphibious ships) as well as many types of logistics and support ships.

2

The Navy’s long-term shipbuilding plans typically cover 30 years, so 2038 is the last year of the 2009 plan, and 2040 is the final year of the draft 2011 plan.

4

Ibid., pp. 10–13. The Navy did not release a shipbuilding plan for fiscal year 2010.

5

A report by the RAND Corporation supports this idea. It concluded that half of the increase in the cost of Navy ships from the 1960s to the mid-2000s was attributable to inflation in the economy as a whole, and the other half resulted from the Navy’s purchase of increasingly capable ships. See Mark V. Arena and others, Why Has the Cost of Navy Ships Risen? A Macroscopic Examination of the Trends in U.S. Naval Ship Costs Over the Past Several Decades, MG-484-NAVY (Santa Monica,Calif.: RAND Corporation, 2006).

6

Steady state refers to a situation in which the inventory of ships theoretically remains constant from one year to the next as new ships replace ones that are retired from the fleet. The average number of ships that would have to be purchased each year to keep the fleet at a given size indefinitely equals that steady-state force size divided by the stated service life of a ship. Thus, a 313-ship fleet divided by an average service life of 35 yields a requirement to buy 8.9 ships a year.

9

For its estimate, CBO divided the total amount of money that it

projected would be necessary for all shipbuilding activities in the 2009 plan—new construction, refuelings of nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and submarines, and other (minor) expenditures—by the number of ships purchased under the plan to determine the average cost per ship. That calculation was made to allow comparisons with the notional budget levels of $13 billion and $15 billion, which CBO assumed would also include all shipbuilding activities. If the calculation used

funding for new-ship construction alone, the average cost per ship under the 2009 plan would be slightly lower. See Congressional Budget Office, Resource Implications of the Navy’s Fiscal Year 2009 Shipbuilding Plan, p. 2.

10

See www.insidedefense.com/secure/data_extra/pdf8/dplus2009_3796.pdf.

11

According to later press reports, the Navy has added five ships to the 2011 plan: one attack sub marine (in 2015), two littoral combat ships (in 2012 and 2013), and two logistics ships (in 2013 and 2015); see Christopher J. Castelli, "Pentagon Restores Submarine, Seabasing in Budget Endgame," Inside the Pentagon (January 7, 2010). CBO’s analysis

does not include those five extra ships, although the testimony that the Congressional Research Service is delivering today does reflect those changes.

13

Christopher J. Castelli, "Navy Confronts $80 Billion Cost of New Ballistic Missile Submarines (Updated)," Inside the Pentagon (December 3, 2009). Later in that article, the average cost of a new SSBN is said to be $6 billion to $7 billion, implying a total cost of $72 billion to $84 billion for the entire class.

14

At around 9,100 tons submerged, a Seawolf class submarine is about 20 percent larger than a Virginia class submarine but only half the size of an Ohio class SSBN.

15

In fact, the requirement for continuous coverage has not yet been established. How much coverage is necessary and how frequently it needs to be in place have not been determined by the Department of Defense.

16

Over the next few years, the Navy may keep BMD-capable ships in their home ports for a much shorter period until more of those ships

19

Because the Persian Gulf takes longer to reach from the United States than Europe does, the Persian Gulf would require a ship-rotation ratio of 6:1 if the ships deployed from Norfolk, Va. (or about 7:1 if they deployed from the U.S. Pacific Fleet). Thus, for eight stations, six ships in the European theater at a ratio of 5:1, plus two ships in the Persian Gulf at a ratio of 6:1, equals 42 ships. For five stations, four ships in the European theater at a ratio of 5:1, plus one in the Persian Gulf at a ratio of 6:1, equals 26 ships. _________________  | |

|   | | MAATAWI

Modérateur

messages : 14757

Inscrit le : 07/09/2009

Localisation : Maroc

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Mer 27 Jan 2010 - 13:53 Mer 27 Jan 2010 - 13:53 | |

|  - Citation :

09:58 GMT, January 27, 2010 NORFOLK, Va. | Navy Cyber Forces (CYBERFOR) was established in a ceremony at Joint Expeditionary Base, Little Creek-Fort Story Jan. 26. Vice Adm. H. Denby Starling II, assumed command of CYBERFOR and continues to serve as commander of Naval Network Warfare Command (NETWARCOM).

Commander U.S. Fleet Forces, Adm. J. C. Harvey Jr., presided over the ceremony and described CYBERFOR as a vital addition to the Navy's warfighting capability.

"I'm very proud to be with you on this journey. You have put your very heart and soul into this command," Harvey said. "I think you will write a glorious chapter in the history of this command as you bring it into the 21st century and bring our Navy along with it."

Starling said that cyber space is more than a path upon which information travels.

"It is warfighting battle space and supremacy in this battle space will ensure that our ships, aircraft and submarines remain dominant in the age of information warfare," Starling said.

CYBERFOR is the type commander for cryptology, signals intelligence, cyber, electronic warfare, information operations, intelligence, networks and space disciplines. CYBERFOR will report to Commander, U.S. Fleet Forces.

As the TYCOM, CYBERFOR's mission is to organize and prioritize manpower, training, modernization and maintenance requirements; and capabilities of command and control architecture and networks; cryptologic and space-related systems; and intelligence and information operations activities; and to coordinate with TYCOMs to deliver interoperable, relevant and ready forces at the right time, at the best cost, today and in the future. CYBERFOR will be headquartered at Joint Expeditionary Base, Little Creek-Fort Story in Norfolk, VA. Location in a fleet concentration area ensures CYBERFOR's close linkage with those it supports.

NETWARCOM will conduct network and space operations in support of naval forces afloat and ashore.

Starling recognized that NETWARCOM's people have laid the foundation for CYBERFOR. That work, he said, prepares the Navy to move to the next level of cyber warfare.

"Many of you contributed to the foundation of CYBERFOR and can take great pride and a sense of accomplishment in the work you've done," Starling said. "The work you do now and will continue to do in the future is of vital importance to ensuring we maintain decision superiority."

Starling is confident that CYBERFOR and NETWARCOM will take the steps needed for the Navy to succeed in battle and in cyber.

"We have seen our nation and America's Navy triumph time and again in the face of equally daunting circumstances," Starling said. "We shall do no less."

|

source:www.defpro.com | |

|   | | MAATAWI

Modérateur

messages : 14757

Inscrit le : 07/09/2009

Localisation : Maroc

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Jeu 28 Jan 2010 - 12:40 Jeu 28 Jan 2010 - 12:40 | |

| - Citation :

- Afghanistan : Le porte-avions USS Eisenhower remplace l'USS Nimitz

L'USS Dwight D. Eisenhower

crédits : US NAVY

|

28/01/2010

Cette semaine, l'USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN 69) a pris la relève de l'USS Nimitz (CVN 68) au nord de l'océan Indien. Le groupe aérien embarqué du porte-avions américain est notamment chargé d'apporter un appui aérien aux troupes déployées en Afghanistan. Depuis son arrivée dans la zone d'opération de la 5ème flotte US, le 18 septembre dernier, les avions du Nimitz ont, ainsi, réalisé 2600 sorties de combat, totalisant 15.296 heures de vol.

Long de 332.8 mètres pour un déplacement de 93.700 tonnes en charge, les porte-avions à propulsion nucléaire de la classe Nimitz peuvent embarquer 68 aéronefs, dont 44 F/A-18. MERETMARINE | |

|   | | Invité

Invité

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Jeu 28 Jan 2010 - 13:50 Jeu 28 Jan 2010 - 13:50 | |

| - Citation :

- $202.7M to Raytheon for 196 Tomahawk Block IV Missiles

Raytheon Co. in Tucson, AZ received a $202.7 million modification to a previously awarded firm-fixed-price contract for procurement of 196 FY 2010 Tomahawk Block IV all-up-round (AUR) missiles.

The Tomahawk AUR missile includes the missile that flies the mission, the booster that starts its flight, and the container (canister for ships and capsule for submarines) that protects it during transportation, storage and stowage, and acts as a launch tube.

The Tomahawk Block IV missile is capable of launch from surface ships equipped with the vertical launch system (VLS) and submarines equipped with the capsule launch system (CLS) and the torpedo tube launch system (TTL)...

Block IV Tomahawk is the next generation of the Tomahawk family of cruise missiles, which began in the 1980s as nuclear strike weapons before being turned into long-range conventional attack missiles. Block IV is the latest variant, incorporating technologies to provide new, flexible operational capability while reducing acquisition, operations and lifecycle support costs. Raytheon began delivering upgraded Block IV missiles to the US Navy in mid-2004.

The Raytheon contract modification provides for 132 VLS missiles, 53 CLS missiles and 11 TTL missiles. Raytheon will perform the work in Tucson, AZ (32%); Walled Lake, MI (9%); Camden, AR (8%); Anniston, AL (5%); Glenrothes, Scotland (5%); Huntsville, AL (4%); Fort Wayne, IN (4%); Minneapolis, MN (4%); Ontario, CA (3%); Spanish Fork, UT (3%); Westminster, CO (2%); El Segundo, CA (2%); Middletown, CT (2%); Largo, FL (2%); Vergennes, VT (2%); Farmington, NM (2%); and various locations inside and outside of the contiguous United States (12.8%).

The company expects to complete the work by July 2012. The Naval Air Systems Command in Patuxent River, MD manages the contract (N00019-09-C-0007).

http://www.defenseindustrydaily.com/2027M-to-Raytheon-for-196-Tomahawk-Block-IV-Missiles-06135/ http://www.defenseindustrydaily.com/2027M-to-Raytheon-for-196-Tomahawk-Block-IV-Missiles-06135/ |

|   | | MAATAWI

Modérateur

messages : 14757

Inscrit le : 07/09/2009

Localisation : Maroc

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Ven 29 Jan 2010 - 10:25 Ven 29 Jan 2010 - 10:25 | |

| - Citation :

- Le porte-avions USS George H.W. Bush reprend la mer

L'USS George H.W. Bush (CVN 77)

crédits : US NAVY

|

29/01/2010

Le nouveau porte-avions de la marine américaine a repris la mer mercredi, pour une nouvelle série d'essais. L'USS George H.W. Bush (CVN 77) a quitté les chantiers Northrop Grumman de Newport News après un arrêt technique de 7 mois. Dixième et dernière unité de la classe Nimitz, le bâtiment a été mis sur cale en septembre 2003 et remis à l'US Navy il y a un an. Après avoir passé avec succès ses essais en mer, au mois d'avril, le porte-avions est entré en cale sèche pour subir une remise à niveau et quelques travaux correctifs. Dans les prochains mois, il va parfaire son entrainement et celui du groupe aérien qui lui sera affecté. Une fois la mise en condition opérationnelle effectuée, le George H.W. Bush sera près, dès cette année, pour son premier déploiement.  L'USS George H.W. Bush ( L'USS George H.W. Bush ( : US NAVY) : US NAVY) Par rapport à ses prédécesseurs, le CVN 77 compte des améliorations, notamment au niveau de la réduction des coûts de fonctionnement. Long de 333 mètres pour un déplacement de 98.000 tonnes en charge, le navire, armé par 5600 marins, embarquera 68 avions et hélicoptères. Il dispose de deux réacteurs à eau pressurisée fournissant une puissance de 205 MW et assurant une vitesse maximale de 31 noeuds. Pour son autodéfense, le CVN 77 dispose, en plus de sa chasse embarquée, de deux lanceurs verticaux (24 missiles ESSM) et deux systèmes surface-air à courte portée RAM. MERETMARINE | |

|   | | Fremo

Administrateur

messages : 24819

Inscrit le : 14/02/2009

Localisation : 7Seas

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Sam 30 Jan 2010 - 19:57 Sam 30 Jan 2010 - 19:57 | |

| _________________  | |

|   | | Invité

Invité

| |   | | MAATAWI

Modérateur

messages : 14757

Inscrit le : 07/09/2009

Localisation : Maroc

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Dim 31 Jan 2010 - 14:47 Dim 31 Jan 2010 - 14:47 | |

| | |

|   | | Fremo

Administrateur

messages : 24819

Inscrit le : 14/02/2009

Localisation : 7Seas

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Mar 2 Fév 2010 - 0:34 Mar 2 Fév 2010 - 0:34 | |

| - Citation :

Northrop Grumman Maritime Laser Clears Design Hurdles

REDONDO BEACH, Calif., Jan. 29, 2010 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE)

The Maritime Laser Demonstration (MLD) system being developed by Northrop Grumman Corporation has passed two milestone reviews by the Office of Naval Research, which point to the real potential of the MLD weapon system design.

Representatives from the U.S. Navy, U.S. Army and the High Energy Laser Joint Technology Office conducted a critical design review and critical safety review of the MLD at the Dahlgren Naval Surface Warfare Center in Dahlgren, Va.

"These reviews indicate that our MLD design should meet the Navy's objectives in future demonstrations," said Steve Hixson, vice president of Advanced Concepts Space and Directed Energy Systems for Northrop Grumman's Aerospace Systems sector. "Next we will finalize detailed test plans and move into land-based, live fire tests."

Northrop Grumman will conduct an at-sea demonstration of this revolutionary capability, according to Dan Wildt, vice president, Directed Energy Systems. "We will prove that the pinpoint accuracy and response capability of our MLD system can protect Navy ships and personnel by keeping threats at a safe distance. We will accomplish this while leveraging technologies with proven scalability that may ultimately enable addressing additional threats of interest to the Navy."

The company received a contract from the Office of Naval Research in July 2009 to demonstrate an innovative laser weapon system by the end of 2010 suitable for operating in a marine environment and able to defeat small boat threats, and ultimately could be applicable to other self-defense missions.

The indefinite-delivery/indefinite-quantity MLD contract has a ceiling value of up to $98 million and an expected overall completion date of June 2014.

Deagel _________________  | |

|   | | Fremo

Administrateur

messages : 24819

Inscrit le : 14/02/2009

Localisation : 7Seas

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Mar 2 Fév 2010 - 21:22 Mar 2 Fév 2010 - 21:22 | |

| Pour le budget 2011 il est prévu la commande de : 2 SSN Virginia 2 DDG-51 Burke 2 LCS 1 MLP 1 LHA (R) 2 JHSV (1 USN + 1 USMC) Suivant le Quadriennal defense review de février 2010, pourrait être abandonné : - EPX, remplacant du EP-3 Orion - CG(x) Futur croiseur Pourrait être financé : - L'achat de 26 EA-18G supplémentaire - 50 M $ pour le prolongement des EA-6B Prowler Sinon, voici la vision de la navy pour 2015 (suivant le QDR) : " 10 to 11 aircraft carriers.  " Nine to 10 carrier air wings. " 84 to 90 large surface combatants, including 19 to 32 BMD-capable combatants. " 14 to 28 small surface combatants. " 29 to 33 amphibious warfare ships. " 51 to 55 attack submarines. " Four guided-missile submarines. " Three maritime pre-positioning squadrons. " 30 to 34 combat logistics force ships. " 17 to 24 command and support vessels (including JHSV). PLus d'infos ici : http://www.finance.hq.navy.mil/fmb/11pres/books.htm_________________  | |

|   | | FAMAS

Modérateur

messages : 7470

Inscrit le : 12/09/2009

Localisation : Zone sud

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Jeu 4 Fév 2010 - 2:03 Jeu 4 Fév 2010 - 2:03 | |

| - Citation :

- Lockheed Martin Delivers 50th MH-60 R Helicopter

Lockheed Martin in Owego marks a milestone today with a delivery to the U.S. Navy.

It turned over the 50th MH-60 R Multi-Mission Helicopter this morning.

As Action News reporter Gabe Osterhout tells us, this chopper is one of the most capable in the world.

Hundreds of Lockheed Martin Owego employees came together to say goodbye to this MH-60 R helicopter.

The company teamed up with Sikorsky to build it.

Lockheed installed the electronics and also made sure everything on-board is properly working.

"We make the systems easier to operate. We provide the capability of seamless integration that takes a whole lot of information coming in from these high tech sensors that would overwhelm a 3 person crew and basically put it into a manageable form so these crews can operate and fight this system effectively," says George Barton, Lockheed Martin's Director of Naval Helicopters program.

Captain Dean Peters of the U.S. Navy says these are the most advanced maritime choppers in the nation's fleet, and the entire world.

"The aircraft is able to just make tremendous capability increases in our ability to detect submarines," Peters says.

These helicopters won't only be used in war time, they'll also be used for humanitarian efforts.

"This aircraft provides an incredible search and rescue capability just because of the systems that if has on board. I mentioned the radar. I mentioned the infrared camera. I mean that's going to help you locate survivors in all kinds of weather, whether it's day or night, it doesn't matter," says Peters.

The Navy says it hopes to add 250 more of these handy helicopters to its fleet.

In Owego, Gabe Osterhout, WBNG-TV Action News.

The crew is expected to leave Owego tomorrow morning for the Naval Air Station in Jacksonville, Florida.

Lockheed expects to build and turn over 28 more MH-60 Rs to the Navy by the end of the year.

http://www.wbng.com/news/local/83482852.html

_________________

"La stratégie est comme l'eau qui fuit les hauteurs et qui remplit les creux" SunTzu

| |

|   | | MAATAWI

Modérateur

messages : 14757

Inscrit le : 07/09/2009

Localisation : Maroc

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Jeu 4 Fév 2010 - 10:04 Jeu 4 Fév 2010 - 10:04 | |

| Dit fremo, c'est quoi un MLP.  | |

|   | | H3llF!R3

Colonel

messages : 1600

Inscrit le : 23/05/2009

Localisation : XXX

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

| |   | | MAATAWI

Modérateur

messages : 14757

Inscrit le : 07/09/2009

Localisation : Maroc

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Jeu 4 Fév 2010 - 10:28 Jeu 4 Fév 2010 - 10:28 | |

| - Citation :

DDG 51 may see revival as US Navy seeks DDG 1000 program halt.

Report to US Congress on Annual 30-Year Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels

08:48 GMT, February 4, 2010 This year’s report reflects the naval capabilities projected to meet the challenges the nation faces over the next three decades of the 21st century. The structure requirements articulated in this report are based upon the 313-ship force originally set forth in the FY 2005 Naval Force Structure Assessment that was reported to Congress and referred to by the Chief of Naval Operations in his FY 2009 budget testimony, as amended by decisions made by the Secretary of Defense in the FY 2010 President’s Budget as well as decisions made during the 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR). As such, the battle force inventory presented in this plan is designed to provide the global reach; persistent presence; and strategic, operational, and tactical effects expected of naval forces within reasonable levels of funding. Consistent with the 2010 QDR, expanded requirements for irregular warfare support, ballistic missile defense (BMD), and intra-theater lift drive the near-term force structure and will necessitate a new Force Structure Assessment.

Background

The Future Years Defense Program (FYDP) and long-term plans submitted by the Department of the Navy (DoN) in this document are shaped by four key strategic priorities outlined in the 2010 QDR:

• Prevailing in today’s war;

• Preventing and deterring conflict;

• Preparing to defeat adversaries and succeed in a wide range of contingencies; and

• Preserving and enhancing the All-Volunteer Force.

To accomplish these priorities, the DoN’s future battle force must be able to accomplish or contribute to the following six key joint missions:

• Defend the United States and support civil authorities;

• Conduct counterinsurgency, stability and counterterrorist operations;

• Build capacity of partner states;

• Deter and defeat aggression in anti-access environments;

• Prevent proliferation and counter weapons of mass destruction; and

• Operate effectively in cyberspace.

Requirements Determination

This 30-year shipbuilding plan uses the 313-ship battle force inventory of the Force Structure Analysis of 2005 as its baseline. This represents the point of departure for implementing several key decisions consistent with the above six missions. Specifically, this plan:

• Shifts the procurement of CVNs to five-year cost centers, which will result in a steady-state aircraft carrier force of 11 CVNs throughout the 30 years but will reduce to 10 CVNs sometime after 2040. In addition, the plan reflects a funding profile of four years of advanced procurement and four years full funding for these strategic assets.

• Solidifies the DoN’s long-term plans for Large Surface Combatants by truncating the DDG 1000 program, restarting the DDG 51 production line, and continuing the Advanced Missile Defense Radar (AMDR) development efforts. Over the past year, the Navy has conducted a study that concludes a DDG 51 hull form with an AMDR suite is the most cost-effective solution to fleet air and missile defense requirements over the near to mid-term.

• Solidifies the DoN’s long-term plans for Small Surface Combatants by announcing a down-select to a single sea frame for the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) program, and by splitting its production between two competing yards. This new acquisition strategy is designed to reduce the ship’s overall cost.

• Maintains an adaptable amphibious landing force of approximately 33 ships. Amphibious ships are proving to be one of the most flexible battle force platforms, as indicated by the high demand for both traditional Amphibious Ready Group operations and deployments of independent amphibious ships for a variety of presence, irregular warfare, maritime security, humanitarian assistance, disaster relief, and partnership building missions.

• Shifts away from a single MPF(F) (Maritime Prepositioning Force (Future)) Squadron optimized for high-end, forcible entry operations toward three Maritime Prepositioning Squadrons with enhanced sea basing capabilities useful across the full range of military operations. Each squadron will have one Large Medium-Speed Roll-on/Roll-off (LMSR) cargo ship (transferred from the Army), and be supported by a T-AKE and a new Mobile Landing Platform (MLP) based on existing designs for commercial ocean-going tankers.

• Transitions to a Combat Logistics Force (CLF) composed of just two type ships: T-AKEs and new double-hulled fleet oilers (T-AO(X)s).

• Cancels the replacement of Command Ships in the FYDP and instead extends the lives of the two existing command ships through at least 2029.

• Expands the size of the Joint High Speed Vessel (JHSV) fleet. With their modular payload bays, these versatile, self-deployable vessels are capable of supporting a wide range of naval missions.

While these decisions implement the strategic guidance promulgated in the QDR, the changes in the strategic environment that prompted them will require the DoN to conduct a new Force Structure Assessment.

Assumptions

Guided and shaped by the foregoing decisions, this plan is based on two key assumptions:

• To be consistent with expected future defense budgets, the Department of the Navy’s annual shipbuilding construction (SCN) budget must average no more than $15.9B per year (FY2010$) throughout the period of this report.

• Between FY 2019 and FY 2030, the DoN must replace the current 14-boat Fleet Ballistic Missile Submarine (SSBN) force with 12 new strategic ballistic missile submarines (SSBN(X)); funding for the SSBN(X) will be included in the SCN core budget.

Long-term Battle Force Inventory Projections

As a key strategic planning document, the Department of the Navy’s 30-year shipbuilding plan strikes a balance between the demands for naval forces from the National Command Authority and Combatant Commanders with expected future resources. Moreover, the plan also takes into account the importance of maintaining an adequate national shipbuilding design and industrial base and strives to be realistic about the costs of ships.

To better explain the future institutional management challenges associated with building a 21st century battle force, this 30-year shipbuilding plan focuses on three different periods. The first, which covers the near-term period 2011 through 2020, is based on a very good understanding of requirements, costs and capabilities. The second period, which covers mid-term requirements projected for 2021 to 2030, is based on a projection of the types of ships expected to be built. However, these ships have yet to be informed by either concrete threat analyses or formal analyses of alternatives, and are therefore necessarily more speculative. The final far-term requirements period, from 2031 to 2040, should be considered no more than the natural outcome of plans based on the decisions and assumptions outlined above, which are certain to change over the next two decades. These three periods will be characterized in the plan by an assessment of projected force levels in 2016, 2028 and 2040 respectively (summarized in Table 1) with these years being illustrative of the overall condition of the naval force in that period.

In the near-term planning period, the Department of the Navy begins to significantly ramp up production of those ships necessary to support persistent presence, maritime security, irregular warfare, joint sealift, humanitarian assistance, disaster relief, and partnership building missions, namely the Littoral Combat Ship and the Joint High Speed Vessel. At the same time, it continues production of large surface combatants and attack submarines, as well as amphibious landing, combat logistics force, and support ships. Yearly shipbuilding spending during this period averages $14.5B (FY2010$), or about $1.5B less than the 30-year average. Nevertheless, because of the relatively low costs for the LCS and JHSV, the overall size of the battle force begins a steady climb, reaching 315 ships by FY 2020.

In the mid-term planning period, the recapitalization plan for the current Fleet Ballistic Missile Submarine inventory begins to fully manifest itself. Current plans call for 12 new SSBN(X)s with life-of-the-hull, nuclear reactor cores to replace the existing 14 OHIO-class SSBNs. Detailed design for the first SSBN(X) begins in FY 2015, and the first boat in the class must be procured no later than FY 2019 to ensure that 12 operational ballistic missile submarines will always be available to perform the vital strategic deterrent mission. Eight more SSBN(X)s will be procured between FY 2021 and FY 2030 (with the final three coming in the next planning period, beyond FY 2031). Because of the high expected costs for these important national assets, yearly shipbuilding expenditures during the mid-term planning period will average about $17.9B (FY2010$) per year, or about $2B more than the steady-state 30-year average. Even at this elevated funding level, however, the total number of ships built per year will inevitably fall because of the percentage of the shipbuilding account which must be allocated for the procurement of the SSBN. In the far-term planning period, average shipbuilding expenditures fall back to a more sustainable level of about $15.3B (FY2010$) average per year. Moreover, after the production run of SSBN(X)s comes to an end in FY 2033, the average number of ships built per year begins to rebound. Together with steps taken in earlier planning periods to increase the service lives of Flight IIA DDG 51s, the overall size of the battle force grows to 301 ships in FY 2040.

Summary

This shipbuilding program described in this report invests where necessary to ensure the DoN’s battle force remains equal to the challenges of today as well as those it may face in the future. The program represents a good balance between the expected demands upon the battle force for presence, partnership building, humanitarian assistance, disaster relief, deterrence, and war-fighting as well as expected future resources. It invests a sustainable average of $15.9B (FY2010$) a year in new ship construction, and maintains an average yearly battle force inventory of approximately 300 ships. The resulting 21st century battle force will help achieve all four strategic priorities set forth in the 2010 QDR, and continue to make vital contributions to all six joint missions outlined above.

(The above is a reproduction of the executive summary of the report. The full report can be downloaded here: http://www.militarytimes.com/static/projects/pages/2011shipbuilding.pdf)

|

defpro.com | |

|   | | Fremo

Administrateur

messages : 24819

Inscrit le : 14/02/2009

Localisation : 7Seas

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Jeu 4 Fév 2010 - 12:19 Jeu 4 Fév 2010 - 12:19 | |

| - MAATAWI a écrit:

- Dit fremo, c'est quoi un MLP.

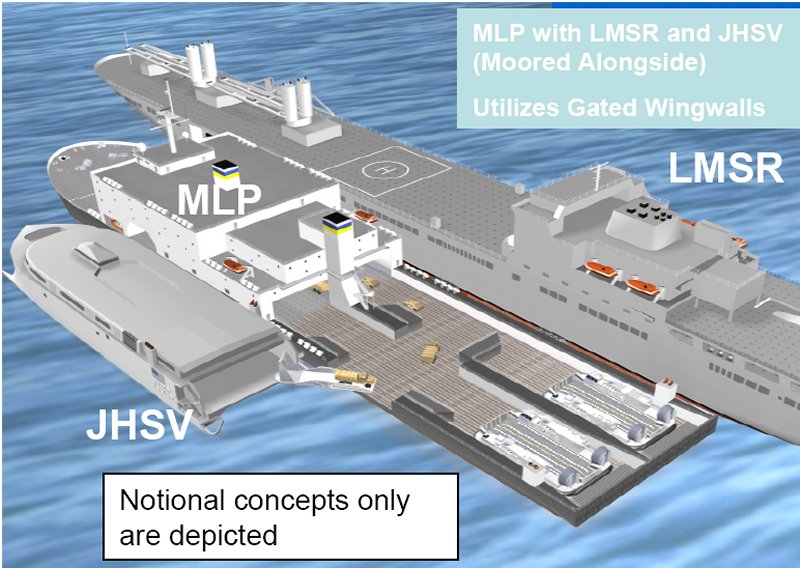

Un MLP, Mobile landing platform, nouveau navire devant servir a l'emport et au déplacement des LCAC en complément des navires prépositionnés. - Citation :

- A second element in the seabase concept is the "mobile landing platform (MLP)", a ship longer than two athletic fields, featuring a large, flat platform. The platform will make the MLP easier for other vessels to load using the platform's cranes and bridges. It will have facilities for almost 1,500 troops, who will be transferred to shore operations with a half dozen landing craft or hovercraft, amphibious tanks and trucks, and a handful of vertical take-off aircraft. The MLP will have ballast tanks, allowing it to sink low in the water to make access by hovercraft easier.

Il servirait d'intermédaire entre les navires prépostionnés (qui doivent utiliser un quai Ro-Ro pour déchargé), les nouveaux LMSR (14 prévu) et la terre grace à l'emport des LCAC Un des concept envisagé :  Il fait partie du MPF(F), Marine prepositionning Force future _________________  | |

|   | | MAATAWI

Modérateur

messages : 14757

Inscrit le : 07/09/2009

Localisation : Maroc

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Mar 9 Fév 2010 - 11:33 Mar 9 Fév 2010 - 11:33 | |

| - Citation :

- Littoral Combat Ship : Le Freedom paré pour son premier déploiement

L'USS Freedom (LCS 1)

crédits : US NAVY

|

09/02/2010

Premier Littoral Combat Ship de la marine américaine, l'USS Freedom (LCS 1) a mené, ces dernières semaines, un entrainement intensif au large de la Floride. Durant ces manoeuvres, les dernières certifications ont été obtenues en vue d'un premier déploiement du navire. L'équipage s'est notamment rodé à la lutte contre les trafics illicites, mission que l'US Navy compte lui confier lors de son déploiement au profit de l'U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM). Ainsi, le bâtiment a embarqué des spécialistes des Coast Guards, rompus à ce genre de mission. Les observateurs ont pu évaluer le Freedom, l'équipage et le détachement aéro, articulé autour d'un hélicoptère Seahawk. Les garde-côtes en ont également profité pour tester la nouvelle embarcation rapide de 11 mètres mise en oeuvre par le bâtiment. La semaine dernière, le LCS 1 a également participé à des entrainements de groupe avec le porte-avions USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70), qui rentrait d'Haïti, ainsi que le croiseur lance-missiles USS Bunker Hill (CG 52). A noter que l'USS Freedom sera basé à San Diego, sur la côte ouest des Etats-Unis.  L'USS Bunker Hill et l'USS Freedom ( L'USS Bunker Hill et l'USS Freedom ( : US NAVY) : US NAVY)  L'USS Bunker Hill et l'USS Freedom ( L'USS Bunker Hill et l'USS Freedom ( : US NAVY) : US NAVY) Développé par Lockheed-Martin et Fincantieri, l'USS Freedom a été construit aux chantiers Marinette Marine de Manitowoc. Long de 115.5 mètres pour un déplacement de 3090 tonnes en charge, le LCS 1 peut atteindre la vitesse de 45 noeuds. Ce bâtiment comprend un armement de base articulé autour d'un système surface-air RAM, un canon de 57 mm et quatre mitrailleuses de 12.7 mm. Grâce à l'embarquement de modules interchangeables, il peut être configuré pour la lutte anti-sous-marine, la lutte antinavire ou la chasse aux mines.  MERETMARINE | |

|   | | Fremo

Administrateur

messages : 24819

Inscrit le : 14/02/2009

Localisation : 7Seas

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

| |   | | Viper

Modérateur

messages : 7967

Inscrit le : 24/04/2007

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Dim 14 Fév 2010 - 16:53 Dim 14 Fév 2010 - 16:53 | |

| - Raptor a écrit:

- Oui peut être, je sais que Aegis est très efficace contre les missiles anti navire supersoniques mais je ne sais pas s'il est capable d'en intercepter toute une meute avec liaison de donnée entre les missiles. En tout cas PAAMS serait incapable de le faire selon le dernier test des brits

L'Ageis a été conçu dès le départ pour travailler en multi-canaux, plusieurs formant navire une sorte "d"armure 3D" chaque navire gérant une zone de couverture spécifique ( le système intègre des calculateurs à la puissance phénoménale, mais seulements quelques pour calculer plusieurs trajectoir d'interception, impossible de connaitre exactement le nombre d'interceptions maximum ) si bien que même avec une attaque par saturation ( concept soviètique de base ) il est extrêment difficile de percer "l'armure".  Et avec le prochain upgrade des DDG du standard Flight I au standard Flight IIB, je vois aucun système d'arme actuel capable de percer cette défense...  _________________  | |

|   | | Fremo

Administrateur

messages : 24819

Inscrit le : 14/02/2009

Localisation : 7Seas

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Dim 14 Fév 2010 - 20:33 Dim 14 Fév 2010 - 20:33 | |

| Photos J. Montoro Fort, de Donald Cook en visite à Barcelone du 29/01/2010 au 03/02/2010. Entrant dans le port aux premières heures de la matinée.    Rowed l'entrée sud du port le jour du départ.  Le Rio Santa Eulalia dans des fonctions d'escorte.  _________________  | |

|   | | Fremo

Administrateur

messages : 24819

Inscrit le : 14/02/2009

Localisation : 7Seas

Nationalité :

Médailles de mérite :

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  Mar 16 Fév 2010 - 19:16 Mar 16 Fév 2010 - 19:16 | |

| | |

|   | | Contenu sponsorisé

|  Sujet: Re: US Navy Sujet: Re: US Navy  | |

| |

|   | | | | US Navy |  |

|

Sujets similaires |  |

|

| | Permission de ce forum: | Vous ne pouvez pas répondre aux sujets dans ce forum

| |

| |

| |

|